The following is an excerpt from the novel The Shanghai Friendship Store* by Susan Ruel. It chronicles the experiences of a small foreign community living in Shanghai in the 1980s (the heyday of Friendship Stores). These state-owned stores used to be quite an exotic thing in China — one of the only places where foreigners traveling on business or a longer visit could buy souvenirs to take back home.

Friendship Stores appeared in the 1950s and sold Western items, like peanut butter and Hershey bars, as well as prestige items like expensive Chinese art and crafts. Only people with foreign passports were allowed to shop there. Since these stores were then the only places where you could buy foreign goods, paying a bit more was a trade-off made gladly by shoppers, who cherished their purchases. Nowadays, however, only a few of these stores remain open, notably in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, and these modern Friendship Stores even feature Western franchises like Starbucks, Baskin-Robbins, etc.

‘The Shanghai Friendship Store’ Chapter 1: A Chinese Eleanor Rigby

Later that winter of 1982, every Sunday night a crushing dread would overtake the so-called “foreign experts” of Shanghai: our small group of Americans, Germans, and French, with a lone Spaniard, Portuguese, and Greek. Our angst would build until the following morning, when we arrived by minibus at the frozen grounds of the college. As if attending a funeral, we waddled into the Foreign Languages Department building dressed in three or four layers of long underwear, thick sweaters, and brightly colored, absurdly garish embroidered silk jackets, padded with camel’s hair. No Chinese local had yet explained to us that these garments should be worn with drab cotton covers.

In three pairs of socks with oversized black felt shoes (except for Maria of Portugal, who mysteriously braved the cold in one of the countless pairs of high-fashion slingbacks), we would pad through concrete hallways as dark and gelid as refrigerators until we reached our offices — the only rooms in that part of Shanghai (across the city from our living quarters in the Maoming Hotel) where it was permissible to burn coal for heat. Holes had been smashed in our office windows to let out the filthy smoke. With our bodies clumsily bandaged against the same iciness that our students endured all day and night through the winter — until it gave them chilblains — we would teach for another winter Monday. By the end of the day, the sorrow of having begun yet another week there would pass, like a piece of hard candy that a child swallows the wrong way, then endures discomfort as it slowly melts in his windpipe.

But a day or so after my arrival in late August, when my interpreter Little Huang took me out to see the campus for the first time, it was still too uncomfortably warm and humid for anyone but mad dogs and “foreign experts” to make their way there. Mounds of rusting machinery were strewn everywhere. The students, assigned to do manual labor before classes began, were using oddly shaped contrivances to sift dirt. Even the palm trees looked dusty and unhealthy somehow, quite unlike the exotic palms of the tropics. They seemed emblematic of the city’s squalor, with its dirty air and water.

Already I had packed away or thrown out all the white summer clothes I’d brought. They’d seemed so fresh and cool-looking back home. In Shanghai, moments after I wore them out in public, they got covered with dull gray scum. Every dingy surface seemed coated with incalculable layers of contamination. The whole atmosphere brought to mind Times Square subway station at rush hour, back in the days before New York City went through its own transformations, as Shanghai would later do, and is doing still.

In those years not long after the Cultural Revolution, classrooms in the Foreign Languages Department displayed peeling, decaying propaganda posters that said things like: “Speed Up Industrial Development,” or “Everlasting Spring to Our Motherland.” To me, the school’s physical plant had the look of a troubled high school in Appalachia, untouched by federal funding.

As we marched down hallways plastered with propaganda posters in the European languages being taught there by Angelique, Fritz, Esperanza, Irini, Maria of Portugal, Garda, my fellow Americans Lennie, Jeffrey, Lorraine, and me, we passed doorways behind which all sorts of strange activities were rumored to be going on, even before Fall Semester began. In one office, young men wearing filthy sleeve protectors over their frayed shirt sleeves were using ineffectual-looking scales made of string to weigh bundles packed into bulging laundry bags. Once the school year officially got underway, we couldn’t help but notice even more sinister goings-on, like the weekly, closed-door meetings, always referred to cryptically as Political Study. An office door might be half-open and before it quickly slammed, we foreigners would catch a glimpse of our Chinese colleagues inside, seated at a table and casting suspicious glances at passersby, as if we could understand whatever we might have overheard.

The Foreign Affairs Office was presided over by a sour-faced, exhausted-looking, old cadre named Mrs. Zhang. It was rumored that she’d gotten the job due to her unusually virulent xenophobia. According to my very limited knowledge of elementary Chinese, the syllable “zhang” meant “dirty.” Of course, the word had a hundred meanings in various tones, but I couldn’t help but chuckle at what it then meant to me. Like old Chen, the cadre who served as titular head of the English department, Mrs. Zhang spoke very little English. The heavily stilted dialogue with which we made our introductions, with help from Little Huang, featured her comment: “China will always love her friends, but will never cease to hate her enemies!”

Mrs. Zhang wore a white blouse and navy blue jacket that I came to recognize as the uniform of politically correct Chinese women of a certain age and station. Coincidentally, it was similar to the outfit I’d worn growing up, attending Catholic school. She wore not a trace of makeup. Her eyes were not enlivened by the slightest gleam, let alone by artifice. They had no more expression than the dark beads on an abacus performing endless, monotonous mathematical calculations. Her skin had the look of an over-laundered garment. Her face was jowly and resembled that of a catfish. Clearly, she’d been through a lot.

In an office across the hall from mine, and just next door to a women’s restroom that featured one Western-style flush toilet and heaps of bloody rags, sat a tiny, forlorn-looking figure — a local woman who was one of my fellow English professors. Her name was Ren, so to me, she became Mrs. Wren. Little Huang explained that Ren means “duty” or “responsibility” and is one of the so-called “hundred old names” of China. Little Huang said Mrs. Wren had graduated from Smith College many years earlier and come home to the motherland to teach English literature. Mrs. Wren looked as pitiful and fragile as a bird, her eyes milky with grief and sputtering like candles, her old clothes and hair both tinged with gray.

Once Mrs. Wren’s family had owned a mansion inherited from her counter-revolutionary merchant father. But everything the family possessed had been confiscated after Liberation in 1949. Her husband, according to Little Huang, “had not been very brave.” A once-prominent scientist, he’d been unable to bear the humiliations of being forced to clean latrines and wear a dunce cap. And, as Little Huang put it, “Mrs. Wren misguesses the looks in people’s eyes.”

We entered her office, where she sat preparing yet another year’s lectures on the only book she taught anymore, Milton’s Paradise Lost. Her eyes bore an exiled expression. She looked even more foreign and out of place there than I did. I looked closer and saw that she was in tears.

“Are you OK?” I blurted out.

She recovered quickly, trying to smile. “I’m weeping over the brilliance of my students,” she murmured, looking down at her papers. Then she changed the subject, inviting Little Huang to come over and spend an evening with her soon — an odd but touching request. Little Huang later mentioned that the Party had recently tried to give Mrs. Wren back her family’s mansion, but she returned it to the authorities once more. Like an anchorite, she slept on a floor mat in a dormitory room on campus.

Sitting in my office, I pondered the fact that the 350 students I was assigned to teach U.S. history and literature had no textbooks. All they had were some ragged copies of the same stilted British English reader that trained the Chinese boys I had encountered already along the Shanghai waterfront, where they practiced English with foreigners.

For my American lit. class, I picked out a few short stories that could be typed on mimeographed sheets by the Institute’s battalion of female typists. I’d soon learn that they were among the few Chinese who actually did much work on behalf of the English Department. Unfortunately, their products were fraught with thousands of typographical errors. A lot of the material they printed for me ended up as toilet paper, the only variety available on campus.

Leaving the college in a big black taxi, a Russian automobile that recalled cars my father had driven in the 1950s, I passed a phalanx of students doing manual labor. While on break, they were obliged to perform calisthenics in unison to the sound of a loudspeaker, like Milton’s Satanic armies mustering on fiery plains.

By the time Spring Festival rolled around (in late January, which seemed incongruous to us foreigners), I started making some fairly subversive political statements in lectures to my U.S. history class, attended by about 250 students. It seemed that they were barely listening, however. Only twice did they react to anything I said.

Once I played a recording of the old spiritual “Motherless Child” and described how, after the Civil War, many freed slaves made the trek North, and more than a few ended up homeless and dying on the streets of New York City. For some mysterious reason, the entire hall full of students burst out laughing. Another time, I presented what I thought was an internationally acceptable short history of the Korean War. The whole room hissed.

I showed photographs of the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, and the Grand Canyon, and I read them passages from American literary classics like Giants in the Earth. Stirred by mawkish homesickness, I contemplated the hardships suffered by pioneers out West: burying their children in a trackless wilderness, trudging onward, killing Native Americans, then perishing in the snow.

“We want to see pictures of skyscrapers, not nature!” my students complained.

It was still frigid and wintry on campus. To keep out draughts, doorways all over Shanghai were shrouded in heavy blankets that made me think of medieval arrases. The cement floors and walls of the college buildings retained cold like an icebox. Even though spring was on its way, and the artificial swelling caused by wearing of so many layers of Chinese long underwear seemed to subside week by week, I still had to don unsightly, mud-colored down mittens, as clumsy as boxing gloves, and three pairs of socks just to make it through the day. Among the “foreign experts,” only Maria of Portugal appeared for work each day dressed with inexplicable elegance, shod in sheer hosiery and fine Italian footwear.

One day I was holding class in my tiny office, into which I’d invited 50 students to warm themselves at my coal stove. Little Huang came in to protest that the dean wanted us back in the classroom. I said that we all felt too cold to study in a room without heat.

“You were told that it would be cold here when they wrote to you in America, to describe the teaching conditions,” she said.

“You didn’t tell me my students would be living in a state of emergency.”

I was pleased with the transformation in my teaching methods, however. I’d worked all winter to change the way class functioned, so I’d be lecturing less and the students would be speaking more and more English. I asked each one to prepare a brief oral report based on a China Daily news story. A government organ that was filled not with real news but with hot air, China Daily irritated me a great deal. Its banner headlines devoted to such “news” as the 100th anniversary of the birth of writer Lu Xun struck me as obvious diversionary tactics.

But the deficiencies of China Daily didn’t seem to bother the students. Using such government propaganda sheets as object lessons, I tried to teach about logical fallacies and faulty reasoning. Taking a deep breath, I told them that a lot of what passed for conventional wisdom about Chinese history before and after Liberation offered classic examples of “black and white fallacies.” Quaking in my padded felt shoes, I dared to read them a quotation from John Stuart Mill: “A state which dwarfs its men so that they may be more docile instruments in its hands, even for beneficial purposes, will find that with small men, no great things can really be accomplished and that the perfection of machinery to which it has sacrificed everything will, in the end, avail it nothing.”

I expected to be struck dead by the gods of communism, but nothing happened. Until the next morning at least, when I was confronted during class by Mr. Xu (pronounced Shoe), the spy who’d turned so many of his classmates into Mrs. Zhang for accepting my invitation to see One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest at the U.S. Consulate. (She had deemed it an “anti-communist” movie.)

“You seem to be in low spirits these days,” Mr. Shoe began.

“You’d be in low spirits, too, if you had ‘sunk from prosperity into poverty. Only in such circumstances does one begin to understand the meaning of life,’” I said, trying to joke about my depression by quoting the writer Lu Xun. In actuality, I was shocked at how the frustrations and isolation of life as a Westerner in China were eroding my social skills and sanity.

“We students wish you would teach the way you used to do,” he said. “Your teaching method has changed quite a lot. It no longer resembles how you taught when you arrived at our school. We Chinese are shy by nature. We do not prefer to appear at the head of the class to speak and ask questions. We prefer grammar drills.”

I tried to debate this point with Mr. Shoe, but found to my disappointment that most of the students agreed with him — or were too intimidated by his political connections to contradict him. They did manage to engage in some lively controversies regarding the plots and characters of a Joyce Carol Oates story about a teenage junkie. So much for “spiritual pollution,” a favorite buzzword of Chinese politics in those days.

Apart from Mr. Shoe, I did manage to draw closer to some of my students. Mr. Lee “Study from Peasants” (as his first name was translated), was a laughingstock among the snobbish Shanghainese because of his rural upbringing. One day, he performed some music in class. At lightning speed, he played a folk song on his erhu – a two-stringed Chinese violin. From time to time, certain other students would confide in me about experiences they’d endured, being sent down to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution. Miss Jiang Lanxing told how, at age 11, she’d been required to dig ditches using only a cheap metal spoon. Another student told how her grandfather, a former teacher (and hence, a class enemy), was tortured by being strangled to unconsciousness and then revived, again and again. The fact that as young Chinese adults, they had the innocent manners and child-like looks of American pre-teens, only made their horror stories harder to hear.

One afternoon, a visiting American professor was invited to lecture on, of all things, “The Fabulist Tradition in Contemporary Western Literature.” She was introduced by a strangely stone-faced Mrs. Wren, who’d been one of her old college classmates back at Smith College. Moments before the talk began, Mrs. Wren was embarrassed by a janitor. Before he would allow the lecture to start, he insisted that she erase a huge blackboard at the front of the hall.

Used to being ordered around by illiterate workers with blameless class origins, Mrs. Wren nevertheless seemed humiliated in the presence of her old classmate, who silently watched the groundskeeper bully the fragile teacher. I can still see Mrs. Wren’s frail arms ineffectually pushing an eraser up and down across the broad expanse of the board. We foreigners who were present in the hall intervened and one of Mrs. Wren’s more tender-hearted pupils stepped in to finish erasing. While introducing her old friend, Mrs. Wren dared venture a cryptic remark: “These dear students are just like broken flowers.”

The visiting professor launched into a long, humorless talk, rife with academic jargon, about how the Cinderella story could be traced to an Egyptian myth. Even we native English speakers found it only fleetingly intelligible. The students seemed more intent on studying the guest’s Ultrasuede ensemble and tasteful matching shoes and handbag than on challenging her arguments.

Just as the lecturer was displaying a book about Cinderella that she said had been handmade by an elderly American “storyteller” in southern Indiana, a stifled cry and a mysterious thud were heard, from just outside the lecture hall. Oblivious to the foreign guest, the students rushed outside. Mrs. Wren’s crumpled form was lying in the dust.

She must have slipped out of the hall unnoticed during the question-and-answer period and jumped from the roof of the low, one-story auditorium. She had fallen on top of some rusty equipment being used to “beautify” the grounds.

I could hardly bear to look at her lying motionless in a misshapen heap. In the confusion, we tried to flag down a passing car, to serve as an ambulance. Ultimately, to save time, we lifted Mrs. Ren into the back of a wretched pedicab cart that transported her to a hospital.

Little Huang and quite a number of young women students crowded around, wailing inconsolably and drying their eyes with little handkerchiefs. Mrs. Wren was greatly loved, and they were taking a political risk by grieving openly for someone who’d committed what could be deemed a counter-revolutionary act. The mystery was why Mrs. Wren had waited until that particular afternoon to try to end a life that had caused her so much pain for so long. Maybe it had something to do with the arrival of her old schoolmate, whose presence might have reminded her exactly how much she’d sacrificed for the “motherland” — to which she’d returned after studying abroad the way a battered wife returns to her spouse.

Some of us were hysterical, others in shock, and most seemed even more numb and stoic than usual. Our questions on where Mrs. Wren had been taken fell on deaf ears, and we foreigners were herded onto the minibus back to our hotel. It felt that afternoon as though the misery simmering beneath the surface all winter had finally broken into grotesque buds.

To be continued…

The Shanghai Friendship Store ©2019 Susan Ruel, all rights reserved.

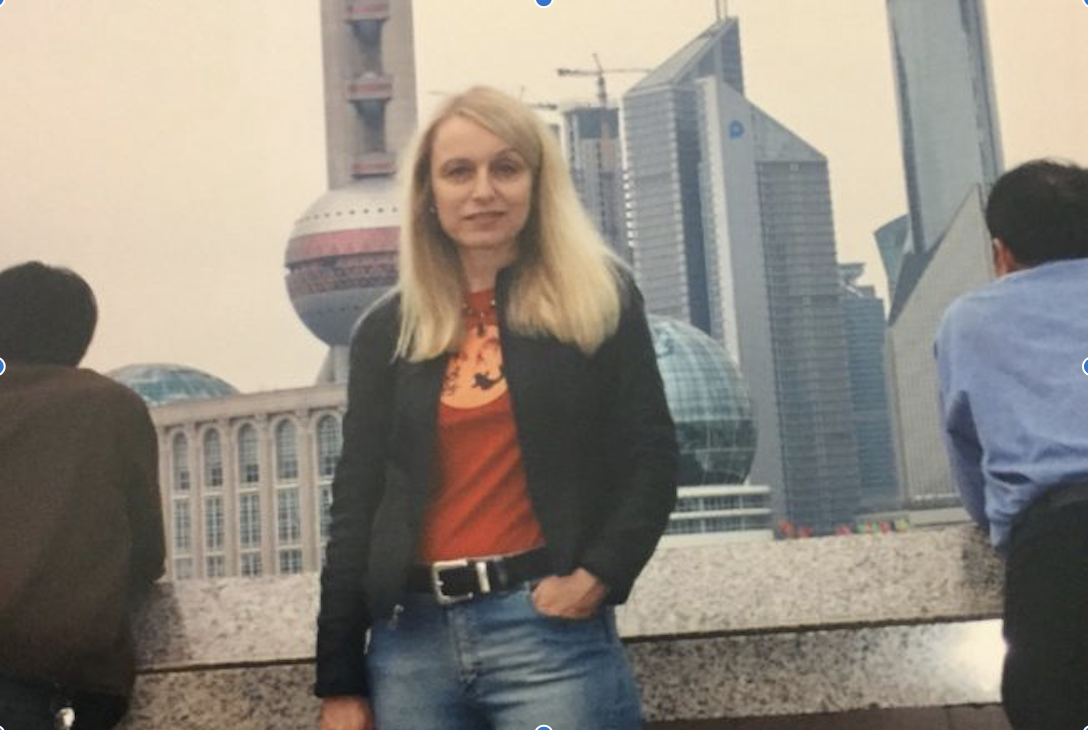

About the Author

Susan Ruel “has worked on the international desks of the Associated Press and United Press International and reported for UPI from Shanghai, San Francisco, and Washington. A former journalism professor, she co-authored two French books on U.S. media history. A Fulbright scholar in West Africa, she has served as an editorial consultant for the United Nations in New York and Nigeria. Since 2005, she has been writing and editing for healthcare non-profits in New York.”

Important Note: The work appearing herein is protected under copyright laws and reproduction of the text, in any form, for distribution is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured through the copyright owner.

Follow us on Twitter or subscribe to our weekly email