How do galaxies such as our Milky Way come into existence? How do they grow and change over time? The science behind galaxy evolution has remained a puzzle for decades. Still, a University of Arizona-led team of scientists is one step closer to finding answers thanks to supercomputer simulations.

Observing real galaxies in space can only provide snapshots in time, so researchers who want to study how galaxies evolve over billions of years have to revert to computer simulations. Traditionally, astronomers have used this approach to invent and test new theories of galaxy formation one by one.

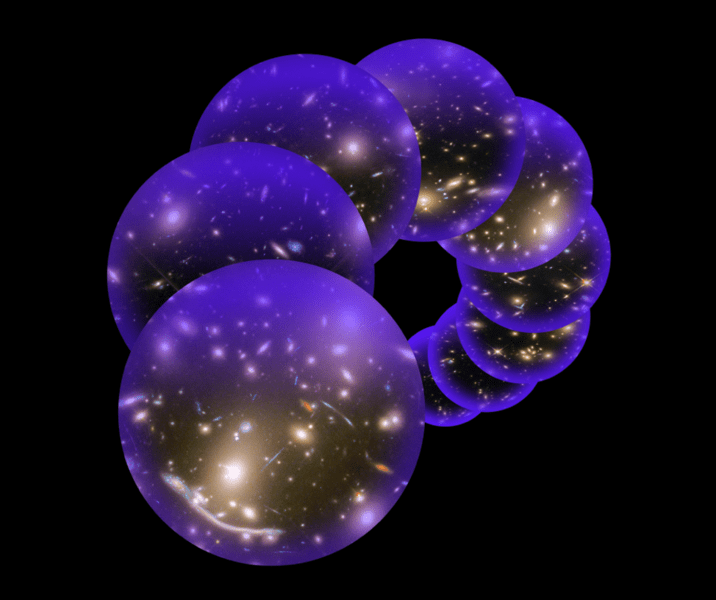

Peter Behroozi, an assistant professor at the UA Steward Observatory, and his team overcame this hurdle by generating millions of different universes on a supercomputer. Each universe obeyed different physical theories for how galaxies should form.

The findings, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, challenge fundamental ideas about dark matter’s role in galaxy formation, how galaxies evolve over time, and how they give birth to stars. Behroozi, the study’s lead author, said:

“On the computer, we can create many different universes and compare them to the actual one, and that lets us infer which rules lead to the one we see.”

The study is the first to create self-consistent universes that are such exact replicas of the real one — computer simulations that each represent a sizeable chunk of the actual cosmos, containing 12 million galaxies and spanning the time from 400 million years after the Big Bang to the present day.

Each “Ex-Machina” universe was tested to evaluate how similar galaxies appeared in the generated universe compared to the actual universe. The most similar universes to our own had similar underlying physical rules, demonstrating a powerful new approach to studying galaxy formation.

The “UniverseMachine” results, as the authors call their approach, have helped resolve the long-standing paradox of why galaxies cease to form new stars even when they retain plenty of hydrogen gas, the raw material from which stars are forged.

Commonly held ideas about how galaxies form stars involve a complex interplay between cold gas collapsing under the effect of gravity into dense pockets giving rise to stars, while other processes counteract star formation.

For example, most galaxies are thought to harbor supermassive black holes in their centers. Matter falling into these black holes radiates tremendous energies, acting as cosmic blowtorches that prevent gas from cooling down enough to collapse into stellar nurseries.

Dark matter in a galaxy

Similarly, stars ending their lives in supernova explosions contribute to this process. Dark matter, too, plays a significant role, as it provides for most of the gravitational force acting on the visible matter in a galaxy, pulling in cold gas from the galaxy’s surroundings and heating it in the process. Behroozi said:

“As we go back earlier and earlier in the universe, we would expect the dark matter to be denser, and therefore the gas to be getting hotter and hotter. This is bad for star formation, so we had thought that many galaxies in the early universe should have stopped forming stars a long time ago.

“But we found the opposite: Galaxies of a given size were more likely to form stars at a higher rate, contrary to the expectation.”

Behroozi explained that to match observations of actual galaxies, his team had to create virtual universes in which the opposite was true — universes in which galaxies kept churning out stars for much longer.

On the other hand, if the researchers created universes based on current theories of galaxy formation — universes in which the galaxies stopped forming stars early on — those galaxies would appear much redder than the galaxies we see in the sky.

Galaxies appear red for two reasons. The first is apparent in nature and has to do with a galaxy’s age — if it formed earlier in the universe’s history, it would be moving away faster, shifting the light into the red spectrum. Astronomers call this effect redshift.

The other reason is intrinsic: If a galaxy has stopped forming stars, it will contain fewer blue stars, which typically die out sooner, and be left with older, redder stars. Behroozi said:

“But we don’t see that. If galaxies behaved as we thought and stopped forming stars earlier, our actual universe would be colored all wrong.

“In other words, we are forced to conclude that galaxies formed stars more efficiently in the early times than we thought. And what this tells us is that the energy created by supermassive black holes and exploding stars is less efficient at stifling star formation than our theories predicted.”

According to Behroozi, creating mock universes of unprecedented complexity required an entirely new approach not limited by computing power and memory. It provided enough resolution to span the scales from the “small” — individual objects, such as supernovae — to a sizeable chunk of the observable universe. He explained:

“Simulating a single galaxy requires 10 to the 48th computing operations.

“All computers on Earth combined could not do this in a hundred years. So to just simulate a single galaxy, let alone 12 million, we had to do this differently.”

In addition to utilizing computing resources at NASA Ames Research Center and the Leibniz-Rechenzentrum in Garching, Germany, the team used the “Ocelote” supercomputer at the UA High Performance Computing cluster. Two thousand processors crunched the data simultaneously over three weeks.

Behroozi and his colleagues generated more than 8 million universes throughout the research project. Behroozi said:

“We took the past 20 years of astronomical observations and compared them to the millions of mock universes we generated.

“We pieced together thousands of pieces of information to see which ones matched. Did the universe we created look right? If not, we’d go back and make modifications, and check again.”

To further understand how galaxies came to be, Behroozi and his colleagues plan to expand the UniverseMachine to include the morphology of individual galaxies and how their shapes evolve over time.

Provided by: Daniel Stolte, University of Arizona [Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.]