Friends All Over the World, from Susan Ruel’s novel Shanghai Friendship Store, portrays the claustrophobic social lives of a small, insular “foreign expert“ community in the 1980s. Shanghai had long been known as China’s most Westernized city. Yet, during this period following the normalization of Sino-U.S. relations, the city’s few foreign residents were discouraged from fraternizing with the Chinese, and vice versa.

My odyssey

Irini, the Greek “foreign expert,” had dark red hair. Her build was small and heavy — not fat, but with no definite shape. A Shanghainese shop clerk once guessed that Irini was Greek just by studying the shape of her nose. Her eyes, darkly speckled like a quail’s, looked as if they should be viewed one at a time, on the side of an ancient vase.

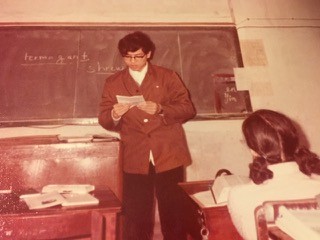

Arriving in Shanghai in October 1982 to become the first Greek teacher in our university’s Foreign Languages Department, Irini found most of her fellow “experts” already a bit bored and disgruntled with life in the foreigners’ ghetto at the Maoming Hotel. She, by contrast, plunged joyously into her first overseas adventure. Irini made friends with her students, a lost tribe of 13 Chinese (like the crew of Odysseus’ wandering ship). They’d been ordered by the authorities to become fluent in Greek.

At first, I viewed Irini with the same detachment as I did the rest of my colleagues in Shanghai. I didn’t yet believe the veteran Spanish teacher Esperanza’s dire prediction that no Chinese would ever really befriend me, that this small village of mostly unhappy foreigners would provide my only society in the world’s largest city.

So initially I — who’d lived as one of the few whites among millions of Africans in Gambia but had never really learned to live all that harmoniously with family and friends back home — almost let superficial trifles create barriers. I couldn’t relate to Irini’s possibly Continental habits: wearing the same outfits for several days at a time, and not washing her hair every day (as most American women did back then). By the third or fourth day, her hair got lank and greasy, almost as if she were Chinese. I misinterpreted these practices as signs of sloth, instead of cultural differences.

But even I was quickly won over by Irini’s sweetness, generosity, and joie de vivre. She spent every yuan of her salary advance adorning her hotel room with Chinese art. Filled from floor to ceiling with scroll paintings, inlaid screens, and porcelain vases; her small, dark cubicle at the Maoming Hotel began to look like a “Friendship Store” — those souvenir shops for foreigners that were omnipresent then at China’s “beauty spots” and historic sites.

In her lavishly decorated apartment, Irini welcomed fellow foreign experts almost every night, after dinner in the hotel dining room. Her fresh flowers, colorful porcelain, and canned fruits with brewed coffee dispelled the morbid chill that seemed to descend on the Maoming Hotel every night, especially after Gate Two was bolted shut at 10 p.m.

Early dinners and the time afterward dragged terribly for foreigners in this city without nightlife. If only the rooms had been outfitted with kitchenettes, so there would be no need to dine out so often. During one of these meals, which often devolved into gripe sessions, Irini told her table companions she was happier in China than she’d ever been. At that point, she’d lived in Shanghai for less than a month.

“That’s very funny, my dear because I am more unhappy in China than I have ever been in my life!” Esperanza shot back.

“Then why do you stay for another year?” Irini asked. It was a question I’d long wanted to ask, but hadn’t dared. (And I was already starting to ask myself: Why not just quit and go home?)

“Because I have friends at my embassy in Beijing. They told me Spain will lose face if I quit and break my contract. Oh, yes! Mrs. Zhang in the Weiban forced me to sign a two-year contract, that bitch!” Esperanza explained, raking long, painted nails through her short, dry hair.

“On May 21 next year, I am going to take the first plane out of Shanghai! These effing people! You can’t imagine how I hate them!” The American obscenities sounded faintly ridiculous, said in a Spanish accent by a lady with pretensions of being a noblewoman. Yet, there was always something slightly humorous about Esperanza when she complained, like a clown with a tragic face.

“You must tell me please, Esperanza, what is this Weiban?” Irini asked with a pleasant, non sequitur smile.

“Weiban? This is the Foreign Affairs Office, my dear. I have been in China for almost 17 months now! I suppose I know what Weiban is!”

Old China hands

Esperanza lapsed into one of her favorite tales: about a Spanish “expert” who’d contracted hepatitis B and then gone mad, staring catatonically at his hotel room wall until he was airlifted home. Not even her Goyaesque vision could quell Irini’s enthusiasm.

“But my students are excellent!” Irini insisted. “They are very respectable, and some are hardworking.”

“Yeah, but it’s such a ‘mafan’ when the school won’t pay for decent textbooks,” Jeffrey remarked.

Sitting silently by Jeffrey’s side and, as usual, devoting full concentration to his meal sat Jeffrey’s Chinese “intern,” a promising postgraduate student named Zhou (pronounced “Joe,” so that’s what we called him). This odd-looking young man with an exceedingly sallow face and tortured eyes was for some reason less reluctant than other Chinese to fraternize with us foreigners.

Joe and his “mentor” were practically inseparable. And Jeffrey, now in his second year of teaching in Shanghai, was less inclined than ever to let anyone forget his “extensive background in Chinese.” In other words, he was now an Old China Hand.

I’d always considered cliquishness to be one of the baser human traits. And it was becoming apparent to me that expatriates in China ranked themselves in as sharply stratified a hierarchy as the Communist Party. Foreigners who’d been there the longest looked down on newcomers, who soothed their vanity by scoffing at the tourists.

At that very moment, Jeffrey was doing his best to discourage the friendly overtures of a couple of grandmotherly matrons from Illinois. On a two-week tour of China and spending their night in Shanghai at the Maoming Hotel, they stopped by our table for a chat.

Jeffrey tried to put them off by launching into a tedious harangue about some textbooks he’d paid for with American dollars and been reimbursed for in local currency.

“Don’t tell me about the books, my dear!” Esperanza said, raising her voice even more. “I am planning to throw all my library into the Huangpu River before I give a single one to these effing people.

Shall I give them to the college, so they can lock them up in the Friendship Room, where students never see them? Oh, yes!” shouted Esperanza. “Do you think our students are allowed to take books from the library? Hah!” she concluded, with a bitter laugh.

At times like this, despite her aristocratic cheekbones and elegant carriage, Esperanza made me think of anecdotes about the singer Bessie Smith, “Empress of the Blues,” feeling her liquor and socking a wealthy white matron in the jaw at a Harlem Renaissance cocktail party.

Just a few weeks had passed since I’d first met Esperanza, and her sense of humor was already wilting noticeably.

“What an experience: living in China for years! Can you imagine! And he speaks perfect Chinese!” gushed one of the senior citizens from Illinois. She was wearing a souvenir People’s Liberation Army cap with a red star.

She seemed oblivious to the fact that Esperanza had just yelled another obscenity in English. Maybe her hearing was not so good. Why, the elderly tourist asked Jeffrey, was it impossible to order fortune cookies here in “Red China”?

The Midwesterner then committed an unpardonable sin, declaring: “We’re the first group of foreigners in China to be allowed to visit the Sacred Mountain of shan.” With that remark, she wore out her welcome, and the conversation quickly came to an end.

“These effing tourists!” Esperanza said after the lady from Illinois had taken a hint and walked away. “They think everything is so wonderful! If I hear one more say that she is the FIRST, I will die. How can she be the FIRST of anything? I have seen a million like her!”

“I hope when I’m as old as they are, I have enough curiosity left to make a trip to China,” Irini said gently.

This is not China

“Where in bloody hell is my rice!” groused a frumpy British expert who sat alone at a nearby table. Margery, a frumpy veteran of several years’ teaching in Shanghai, was on speaking terms with no one.

“I ordered rice nearly an hour ago!” she grumbled to Mao Zedong, a moon-faced Fujianese waiter who waddled toward her table, eternally beaming. A 10-yuan note had just been ripped up and thrown in his face by an irate foreign teacher, convinced that he was being overcharged again, but Mao looked unruffled. He resembled the smiling, bald old man on Chinese lunar New Year greeting cards.

“May I be of service, Madame?” he asked Margery.

“My rice seems to be taking an awfully long time,” she said, mollified by his presence. Mao Zedong was the reason that the experts preferred this drab South dining room to the elaborate, high-ceilinged North restaurant, with its chandeliers, tablecloths, and insolent young waiters, many of whom were rehabilitated Red Guards. Youths formerly assigned to beat up “class enemies” and persecute the “stinking ninth category of intellectuals” had been turned loose on the tourists.

“One hour too long. Too sorry, Madame! I go to check for you right now, okay? Many weddings this season,” he explained, pointing to several huge round tables packed with local Chinese families.

Oddly, the wedding guests appeared to engage in little or no small talk while awaiting their food. Brides could be identified only by their gaudy makeup and new but drab pantsuits.

“Next year is Year of Dog. Everyone wants to marry before that bad luck year!” Mao said, chuckling like Santa Claus.

“Who is this terrible woman?” Irini asked, pained that anyone would give Mao Zedong such a hard time.

“That’s Margery, the old battle-ax!” said Garda, a German expert who was Irini’s closest new friend.

“Brits can be like that. They’re as bad as the French,” Lorraine noted, gesturing toward a huge table across the room. The French experts often congregated there, when they weren’t attending stylish little dinner parties among themselves, serving food whipped up on hot plates in their rooms.

“Irini, why are you only worried about the feelings of Chinese?” Esperanza demanded.

“We must try to separate the people from their government. The government is tyranny, but this not means the people are bad,” Irini replied.

“How many times have we heard that line!” said Jeffrey. “But their government is an expression of the will of these people. The fact that they lack the guts to throw off this system tells you what kind of people they are.

Besides, the lao bai xing are constantly acceding to the wills of tyrannical petty bureaucrats, who suffuse the whole society!” he said as if reading from a prepared statement. His intern Joe nodded solemnly.

“What means this lao bai xing?” Garda asked.

“Please, let’s not be hateful tonight!” murmured Thelma, her eyes brimming. It was the first time she’d opened her mouth all night, and her voice was barely audible. Although Thelma had been in China longer than most, or perhaps because she’d been in China longer, this older woman from Connecticut exuded no air of authority.

Thelma had managed to elude the trap of becoming clannish, I thought, admiringly. But with her bangs chopped off across her forehead (she cut them herself), her grayish skin and downcast eyes, the poor thing looked as if she were battling clinical depression.

“Not to worry, Thelma. We’re just trying to tell these new people that this Friendship stuff is a crock! Except for the students themselves, of course. Your heart just goes OUT to them!” said Jeffrey.

Later that night, Thelma would attend a Chinese opera performance to which the Weiban had invited the “experts.” An American tourist who happened to be sitting directly behind Thelma would feel sick to his stomach, lean forward, and throw up all over her. It was just her bad luck.

A few weeks earlier, I’d already witnessed Thelma break down completely at dinner one night. She was overcome by the sight of so many heaping platters of double-sautéed pork and gu lao rou (sweet and sour pork) being served to foreign “experts” as they complained ceaselessly all around her.

Thelma’s earliest years in China had been spent teaching far to the north, in the bleak, industrial city of Shenyang. Fairly new to Shanghai, she still felt stunned at the sight of so much food — and so much heedless ingratitude for it, on the part of spoiled foreigners. “This is not China!” Thelma sobbed, fleeing the dining room. After the wretched fare I’d eaten, lunching with my students on campus just across the city, I could certainly see Thelma’s point.

Ordinarily, I wouldn’t dare sit at the same huge round dining table with Old China Hands like Jeffrey and Esperanza, who were close friends, and Lorraine who, fresh from a year in the countryside, was still considered a bit of a third wheel.

Nevertheless, Lorraine, as one who’d already spent at least a year in China — albeit in a backwater like the city of Luoyang — was deemed to be a cut above us recent arrivals. Unaware of these subtle social nuances, Garda had dared to sit down with this group of veteran experts. Then, as latecomers to the dining room that night, Irini and I simply followed suit, joining her at their table.

The poorest country in Europe

Maria, the glamorous Portuguese whom I’d first seen dancing in the notorious hotel bar that we called the Snake Pit, sauntered past us. She was clad in a hand-crocheted designer ensemble. Gold-toned jewelry, crocodile shoes, and a cigarette holder completed Maria’s outfit.

“Where is she planning to have that dress dry-cleaned?” Lorraine wondered aloud. Ordinarily, Maria was accompanied everywhere by Fritz, a barrel-chested, gray-haired German expert who’d previously been Esperanza’s constant companion.

On this particular evening, Fritz was nowhere in sight. Instead, Maria was accompanied by a foreign businessman she must have met next door in the exclusive Maoming Club. The price of admission there alone was enough to keep most “experts” out of the club entirely.

Maria always made me think of the wives of conquistadores, trekking through South American jungles in gowns bedizened with pearls. She was like a woman in a dream. One couldn’t help but speculate what she’d look like after six months in China. One couldn’t help but “cherchez l’homme” who’d propelled her to China in the first place.

As the couple passed, I heard Maria telling her escort, “Portugal is a poor country, the poorest country in Europe…” I wondered about the connection, if any, between Maria’s oft-repeated phrase and her tenacious clinging to designer clothes and other trappings of wealth.

Lorraine piped up again: “How did she manage to get all that clothing over here? Can you imagine what her hotel room looks like? Where does she keep it all?”

I thought back on the scene that I’d witnessed just a few weeks into the Fall Semester, during our minibus ride out to the campus one morning. Since Lorraine had “fallen ill” and missed teaching the entire first month of classes, she and Maria were meeting for the first time that day, on the bus to work.

Lorraine almost sparked a riot when she said: “So you’re here to teach the Chinese to speak Portuguese, Maria? I always thought Portuguese was just a mixture of bad Spanish and bad French.”

Until I witnessed Lorraine’s first encounter with Maria, I’d assumed that Lorraine spoke tactlessly only to me. I’d even wondered why it bothered me so much. Why couldn’t I just let it go and forget her rude remark about all the “perverts” she’d met from my home state of Rhode Island? When I saw how Lorraine introduced herself to Maria, I realized that I shouldn’t take personally anything Lorraine said.

Yet somehow Lorraine managed to be fairly popular with most of the other women “experts” in Shanghai. They seemed to view her as gutsy and unpretentious — like some sort of model feminist.

They laughed hysterically at Lorraine’s oft-repeated one-liner about living in the Chinese countryside: “Everyone in Luoyang knew everything about everyone else. They even noticed if you flushed twice!”

Some found it hilarious when Lorraine talked about how, back in her Luoyang flat, she’d held an umbrella over her head while in the bathroom, to ward off the deluge that poured down whenever the “experts” upstairs used their bathtub.

But Lorraine’s anecdotes about life in Luoyang got on my nerves, for some reason. She seemed unaware of how much the experience of living there had coarsened her — if that’s what had coarsened her. I guess I just couldn’t forgive her remarks about Rhode Island.

American pocket

Out of nowhere, Mao Zedong reappeared at our table to present the check. Then dinner in the South Dining Room that evening broke up abruptly, as it usually did.

“We told you: ‘Yige fapiao, Yige ren,” Jeffery fumed, “One receipt per person!”

“Okay, who had a drink?” Lorraine hollered, pulling out a pencil to do some arithmetic.

I thought of Lou Gichuke — my ex-boyfriend back at the University of Iowa — and his scorn for the Americans among his fellow grad students in political science. They were too tight-fisted (and broke) to treat their friends and often made a big production of asking for separate checks. “American pocket,” he called it derisively, using what he said was an East African expression.

At least here in Shanghai, I thought, Jeffrey footed the bill for his intern Joe. For the thousandth time, I tried to imagine what Lou Gichuke might be doing at that very moment, in Iowa City. Considering the 12-hour time difference, he was probably just waking up.

“How come yogurt costs a different price every damn time that I order it? We experts are on a fixed income, you know, and we don’t appreciate getting nickeled and dimed every time we come in here,” Jeffrey griped to the waitress, who nodded emphatically. She spoke no English really.

Thelma sighed and stared at a mural on the dining room wall. It was emblazoned with a familiar propaganda slogan, “We have friends all over the world” in both English and Chinese characters: Quietly placing 2 yuan near her plate, Thelma slipped out of the room. Why hadn’t she sat by herself, or better yet, missed dinner altogether, as she usually did? She should have gone straight to a Chinese opera performance. That would be pleasant, she thought.

If you haven’t yet done so, please read:

The Shanghai Friendship Store: Deep Impressions (Chapter 4)

The Shanghai Friendship Store: The Snake Pit: No Escape (Chapter 3)

The Shanghai Friendship Store: A Floating Life (Chapter 2)

The Shanghai Friendship Store: Eleanor Rigby (Chapter 1, Part 2)

The Shanghai Friendship Store: Eleanor Rigby (Chapter 1, Part 1)

The Shanghai Friendship Store © 2019 Susan Ruel, all rights reserved

Important Note: The work appearing herein is protected under copyright laws and reproduction of the text, in any form, for distribution is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured through the copyright owner.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest