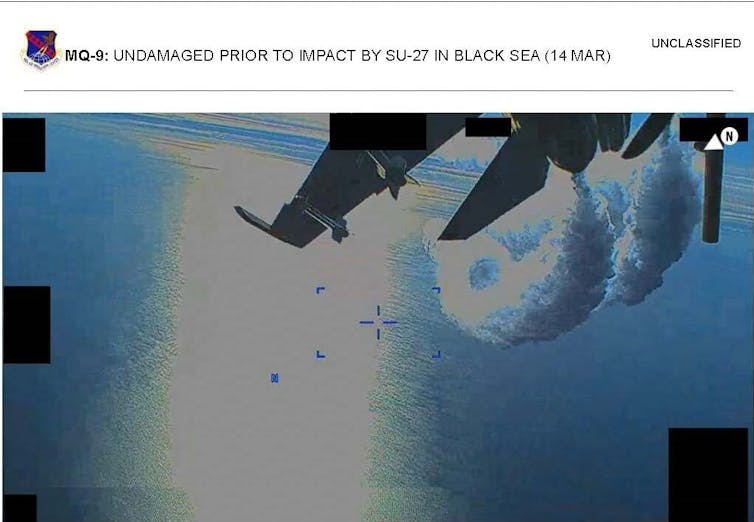

The extraordinary footage of a Russian jet intercepting a U.S. drone over the Black Sea demonstrates just how potentially disastrous such encounters outside actual war zones can be. Released by the Pentagon, the drone’s own video captures the Russian aircraft apparently spraying the drone with fuel, then deliberately colliding with it. The incident matches similar aggressive displays by the Russian air force in the region, the Pentagon claimed.

But beyond such acts of brinkmanship connected to the war in Ukraine, the Black Sea confrontation highlights just how easily these military interactions might lead to war breaking out “accidentally”.

We are seeing these close encounters of the military, naval, and aviation kind increasingly often, too. In 2021, it was reported that Russian aircraft and two coastguard ships shadowed a British warship near Crimea. And last year, Australia’s defense ministry said a Chinese fighter jet harassed one of its military aircraft in international airspace over the South China Sea. The risk of these dangerous “games” triggering something more serious is clear — but there are few rules or regulations preventing it.

Reckless behavior

All militaries must comply with basic international law on questions of safety, but there are large exemptions and separate arrangements that fill the gaps. Historically, the U.S. and Soviet Union led the way in creating some rules to control incidents on and over the high seas during the Cold War. The basic rule was that both sides should avoid risky maneuvers and “remain well clear to avoid risk of collision.” To reduce the risk of collisions, craft in close proximity should be able to communicate and, where possible, be visible. They should not simulate attacks on each other.

Later, Russia copied this agreement with 11 NATO countries, and an Indo-Pacific version — the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea — was added in 2014. While primarily between the U.S. and China, at least half a dozen other countries have promised to abide by it.

Supplementary rules for air-to-air military encounters followed. These usefully added that “military aircrew should refrain from the use of uncivil language or unfriendly physical gestures.” Other rules emphasized professional conduct, safe speeds, and avoiding reckless behavior, “aerobatics and simulated attacks,” or the “discharge of rockets, weapons, or other objects.” The U.S. and Russia added a more specific agreement for Air Safety in Syria during the time they were operating in very close proximity, and when close calls in the air were reported.

But these are all “soft” rules. They’re not treaty obligations with compliance mechanisms, and they are only voluntarily adopted by some countries. Furthermore, there are no precise definitions of “safe” speeds or distances. New technologies — such as drones and other interception techniques — add another level of unregulated complexity.

Missile tests

Few things are as frightening as missiles traveling toward or over another country without consent or warning. The original Soviet-era rule involved mutual notification of planned missile launches. But this only ever applied to intercontinental or submarine-launched missiles, not short-range weapons or missile defense systems.

Aside from some voluntary UN codes, the only other binding missile notification agreement is between Russia and China. China and the U.S. do not directly share launch notification information, nor do the other nuclear powers. Some, like North Korea and Iran, even violate the missile prohibitions directly placed on them by the UN Security Council.

War games and hotlines

Militaries need to practice. But this becomes risky when pretend can look very much like an actual attack — especially when fear and paranoia are added to the mix. North Korea is a modern example of this, but there have been incidents in the past of large-scale wargames almost sparking a nuclear exchange. In 1983, for example, misinterpreted military intelligence led to the U.S. going to DEFCON 1 — the highest of the nuclear threat categories — during a tense period of the Cold War.

There were agreements about the notification of major strategic exercises between the U.S. and Soviet Union, but beyond advance warning, even these failed to set out what best practice actually looks like (such as allowing observers or not allowing an exercise to look identical to a full-blown attack). More importantly, there is no international law governing such questions — perhaps most critically, how leaders should be able to communicate directly, quickly, and continuously.

A “hotline” was first agreed upon in 1963 after the Cuban Missile Crisis. While a direct link doesn’t guarantee the phone will necessarily be answered or the subsequent conversation sincere, it does at least offer a channel to avoid confusion and de-escalate quickly.

A second-tier hotline allowing commanders on the ground to communicate directly is also useful, such as the one now linking Russian and American militaries to avoid an accidental clash over Ukraine. But such dual systems are the exception, not the rule. Nor are hotlines particularly stable — the one between North and South Korea, for example, has been cut and restored numerous times. And they are not mandated by international law — emblematic of a wider situation where the risks of getting it wrong are very real indeed.

Alexander Gillespie, Professor of Law, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest